New Delhi: When Apple and Google announced three weeks ago that they’d developed software to help battle the COVID-19 pandemic, it was a big deal.

The tech giants are fierce competitors. They rarely cooperate. And together, their software controls about 3 billion smartphones, equal to almost 40 percent of the world’s population.

It seemed clever, assuming the privacy implications could be worked out.

The software would silently keep track of people who’d been near someone who tested positive for the virus, prompting those contacts to be tested and quarantined if necessary. The idea was to automate part of a laborious process called contact tracing, which public health officials use to stem the spread of an infectious disease. Thorough contact tracing, they say, is crucial to allowing the world’s economies to reopen without reigniting infection rates.

But few organizations, if any, have ever done contact tracing at the scale that will be required to contain coronavirus.

Software developers flocked to tap the new Apple-Google capabilities. The state of Utah accelerated its work with Twenty, a small New York City-based social media app developer.

Citizen, the developer of a public safety app with 4 million users nationwide, added a contact-tracing function to its app, though it is not yet activated.

Tech executive Aniq Rahman created Zero, a group of about 200 developers and marketers including one of the developers of TraceTogether, Singapore’s contact-tracing app.

And why not? Cities and states were talking about hiring tens of thousands of contact tracers to manually reconstruct the movements of Covid-19 patients.

But it wasn’t clear how these people could be hired and trained quickly enough to be useful.

The Apple-Google software had the potential to do some of the same work effortlessly at a fraction of the cost.

It’s not working out that way. So far at least, the pandemic response has become a bitter lesson in everything technology can’t do and an example of Silicon Valley’s legendary myopia. States like New York, California, and Massachusetts, and cities like Baltimore and San Francisco, have looked carefully at cutting-edge contact-tracing solutions and largely said, “No thanks,” or “Not now.”

Instead, public health officials in hard-hit states are moving ahead to deploy armies of people, with limited assistance from technology.

Massachusetts has budgeted $44 million to hire 1,000 contact tracers. New York State, with funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, said last week it plans to hire as many as 17,000. California is soon expected to announce plans to hire as many as 20,000 contact tracers.

This analog approach will likely be the model nationwide, according to current and former health officials.

Last week, two former federal health officials, Scott Gottlieb and Andy Slavitt, advised the federal government create a massive, and manual, contact-tracing program.

The plan, cosigned by 14 other doctors, scholars, and policymakers, would include $12 billion for up to 180,000 contact tracers; $4.5 billion to house infected and exposed people in vacant hotels; and $30 billion for 18 months of income support for those voluntarily self-isolating.

“There is no silver bullet in the fight against coronavirus,” Slavitt, the former head of Medicare and Medicaid, told NPR. “But if we want to get back to a more normal existence, we need to give states the tools they need to contain the virus.”

“Those of us who have worked in public health for decades kind of cringe when we hear ‘Oh it will be easy. Anyone can do it.’”

It’s not super complicated to understand why technologists are having a hard time getting traction.

Traditional contact tracing has been honed over decades of response to disease outbreaks.

Officials ask patients where they’ve been and whom they’ve been near; they then suggest those people get tested for the disease and make sure they quarantine, if necessary.

Quickly identifying and segregating people carrying the virus can slow the spread of a communicable disease.

“It works by building a human bond between two people,” the patient and the contact tracer, says Tom Frieden, the former head of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the New York City Department of of Health and Mental Hygiene.

“It means actually talking to someone and answering their questions, addressing their needs and concerns, and building, earning, and maintaining their trust and confidentiality.”

In theory, the Google-Apple tech, and similar approaches, can automate and greatly speed the process of identifying contacts. But public health officers are typically MDs and PhDs who aren’t dazzled by cool-looking software, especially if the pitch comes from people without public health backgrounds.

They’re uncomfortable deploying untested technology during a pandemic, when glitches can cost lives.

“Those of us who have worked in public health for decades kind of cringe when we hear ‘Oh it will be easy. Anyone can do it’ or ‘We can replace that with this machine’ you’re waving around,” Frieden says.

Also, too much enthusiasm about technology feels politically risky right now.

Covid-19 has already stretched city and state employees super thin, so the easiest response to a tech pitch is to delay making a decision or to adopt it in baby steps.

Contact-tracing programs are created and managed by politicians and bureaucrats. But it’s no longer universally good for a politician’s popularity to be too closely associated with the titans of Silicon Valley.

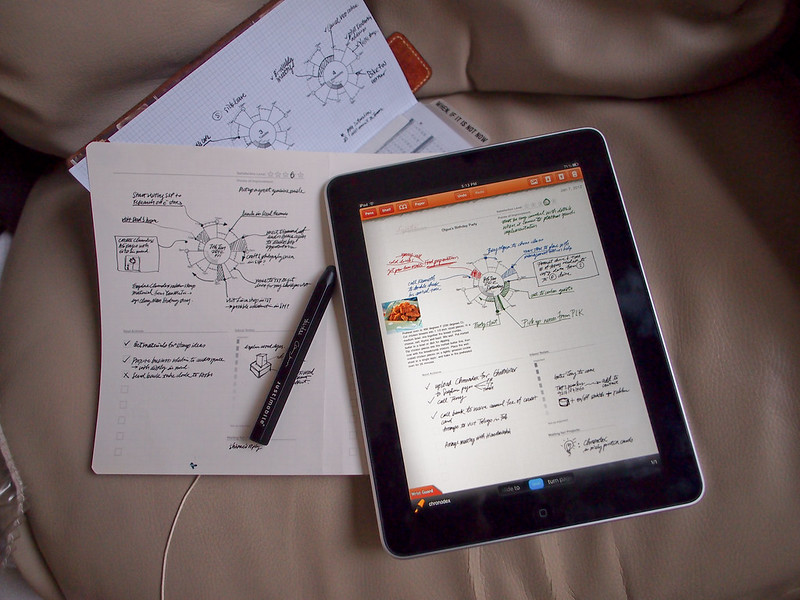

For now, health officials plan more limited uses for technology, such as ensuring that call center workers can access callers’ files after identity verification, or deploying automatic texting systems to stay in touch with those in quarantine and keep tabs on their symptoms. Arming contact tracers with tablet computers can simplify and speed data analysis.

In the short run, the most technologically aggressive government plans will only offer software to extract location data from a patient’s smartphone, making it easier to reconstruct timelines.

Most smartphones automatically record where they’ve been, unless a user disables the feature.

Some states are considering apps that would make it easy to access this data, examine it, and potentially send it to a contact tracer. Knowing where we’ve been can help us remember whom we’ve been with.

Frieden himself is helping guide some of this app development. He’s the chief executive of Resolve to Save Lives, which works on global epidemiological issues and is part of another health nonprofit, Vital Strategies.

Together, they are helping New York state build the three mobile apps it will use in its contact-tracing efforts.

But Frieden says the apps reflect a philosophy that less is more. One will make it easier for contact tracers to match Covid-19 test results with the correct patients.

Proponents of using more technology in contact tracing sometimes point to experiences overseas to support calls for a high-tech approach in the US.

Dig deeper, however, and what’s really going on in places like China, South Korea, Singapore, and elsewhere is less conclusive, or difficult to transplant to the US’s stricter views about freedom and personal privacy.

In China, where the novel coronavirus first emerged, efforts to harness smartphones have been broad-reaching, with few privacy controls. Most visibly, programs that run inside the ubiquitous smartphone apps WeChat and Alipay generate QR codes that reflect a person’s reported symptoms and movements. Officials scan the codes to determine who should be allowed into buildings or public spaces, and who should be ordered to quarantine themselves.

South Korea, another supposed success story, has used technology in ways that are unlikely to fly in the US. Automating the process by which authorities gather data on a person’s movements, from sources including their phones, has reportedly reduced the time required to gather the data from 24 hours to 10 minutes. But South Korea has also issued text alerts containing crudely anonymized information about people diagnosed with Covid-19, and it has deployed an app that alerts officials if someone strays from quarantine—measures far beyond anything being considered in the US.

Singapore was the first country to develop a contact-tracing scheme that uses Bluetooth signals from smartphones to identify contact between individuals, similar to the Apple-Google approach. So far, however, the government says only 1.4 million of the nation’s 4.3 million smartphone users have signed up to use the app.

Frieden notes that behind most of these apps are armies of traditional contact tracers, so it’s not clear—at least to him—that proximity tracing, as it’s called, even works. “You’ll read a lot of misguided stuff on Twitter and elsewhere about ‘This is what Asia did.’ It’s not true. China has done traditional contact tracing on 730,000 people. “

In the US, Utah’s contact-tracing system makes the most extensive use of technology.

In March, the state commissioned Twenty to build an app now called Healthy Together. It aims to more quickly connect contact tracers with people who are Covid-19 positive, and help the infected use their smartphones to build a one-week timeline of whom they’ve been with.

“Once you have this app, it tracks where you go,” Governor Gary Herbert said in introducing the app. “If someone has COVID-19, it can go back and see who you’ve bumped into.”

Roughly 40,000 Utahns have downloaded the app, a little more than 1 percent of the state’s population.

That’s a long way from the more than 60 percent adoption many epidemiologists think is necessary for contact-tracing apps to be effective.

But it will be helpful no matter how many people use it, says Utah Health Department spokesperson Tom Hudachko.

“Our app isn’t going to be sending automatic notifications to people, so it doesn’t matter to us what the saturation is.” He said information the app generates is sent to the state’s 1,200 contact tracers. They can then decide whether to call potentially infected people and urge them to be tested, or to warn a business that it’s hosted a person who tested positive.